As filmmakers, Peter and Bobby Farrelly are outrageous, bodaciously socially incorrect and sometimes crude as hell. But there's also something supremely generous-spirited about them. That may be exactly the thing that derails "Me, Myself & Irene" as a comedy: The picture never builds the same ramshackle momentum that "Dumb & Dumber" and "There's Something About Mary" do, and for the first time the Farrellys don't seem as sure-footed about the tone they want to strike. It's not that they grab for laughs -- it's more that they let them slip by. "Me, Myself & Irene" feels so relaxed that it ends up seeming vague and indistinct. Leaving the theater, I couldn't quell those waves of disappointment: It just should have been funnier.

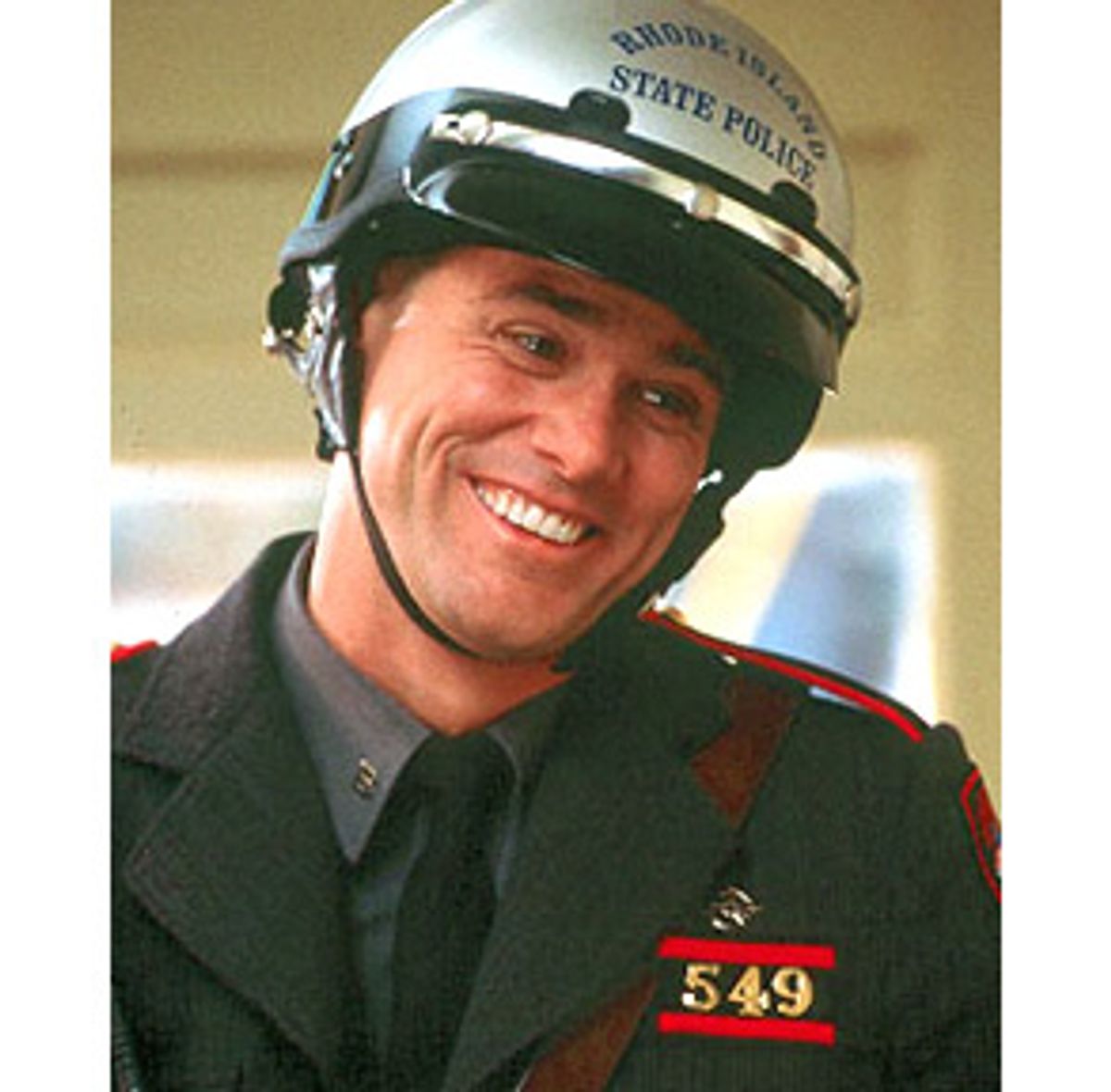

And yet I'm not sure it could be more likable, in its own gangly, off-kilter way. Jim Carrey, as Charlie Baileygates, a sweet-tempered, generous Rhode Island state trooper with a split personality -- his obnoxious, aggressive alter ego goes by the name of Hank -- could carry the movie admirably with his physical comedy alone. But as he's developed the character, and as the Farrellys, along with co-writer Mike Cerrone, have written it, you end up feeling a degree of sympathy for Hank even as you're forced to face up to his more unsavory qualities -- his fondness for footlong dildos, for instance.

That's partly a measure of Carrey's skill as an actor, but it probably has just as much to do with the Farrellys' pervading sensibility. As outlandish as they are, there's a definite skillfulness to their touch -- it was apparent even in their first feature, "Dumb & Dumber," a work of |ber-booger genius.

But there's also a kind of delicacy at work in the Farrellys' movies; the secret is that they have a way of being compassionate that never gets uncomfortably squishy. For one thing, any human being with an infirmity, a deficiency or even just a skin color (any skin color) is fair game for their jokes: They're equal-opportunity pranksters. I'd take that even further and say that what has made the Farrelly brothers' movies so beloved -- as opposed to just successful -- is the fact that people who are "different" don't make them nervous. Most of us grew up with at least one kid who was, as we used to say before we were made to feel anxious about it, retarded, and we can all recall the various ways in which those kids were treated. In my own recollections, everyone would try to be nice to those kids, but no one except the smallest handful really felt relaxed around them. The Farrelly brothers may not always be particularly nice, but the great playground of their work comprises all the cruel tricks that life can spring on us, and they want everyone to feel welcome to laugh and play without any self-pity or awkwardness.

The Farrellys' barbed compassion is evident in "Me, Myself & Irene"; too bad the gags aren't as memorable. Charlie Baileygates is the kind of guy who takes his lumps and doesn't seem to mind them. He looks the other way when his wife takes up with a vertically challenged African-American chauffeur who's also, as she is, a Mensa member. He looks the other way when she gives birth to black triplets (explaining away their dark skin with devil-may-care denials like "My great grandmother was half-Italian"), although he makes no secret of the fact that he adores them. And he looks the other way when his wife leaves him, which is when his troubles begin.

Charlie can't deal with his painful feelings, and so he shoves them into some dark, hidden corner of his psyche, where they fester and eventually reveal themselves in the guise of hotheaded Hank. Hank and Charlie both have the same Marine-style crewcut, but the similarity pretty much stops there. When Charlie snaps, every muscle in his face seems to stretch taut, and the faintly loopy gleam we've seen in Charlie's eyes hardens into a cartoonishly funny, menacing glare. (He looks like something that might have sprung from the pen of Chuck Jones, which gives us a suggestion of how wonderful he might be in his next project, a remake of "How the Grinch Stole Christmas.") Charlie was a patsy, the guy who just wanted everyone to like him; Hank is the id unleashed, the one who barks orders instead of taking them and who throws punches like a demented prizefighter. In short, he's not gonna take it anymore.

Charlie/Hank hooks up with the innocent-looking Irene (Renie Zellweger), who has a wild streak or two of her own, and after a sequence of mix-ups the two end up on the run from the law -- and falling in love. The plot doesn't matter much; the Farrellys, bless their hearts, can't tell a story to save their lives. That's not a problem if the gags sparkle and if you've got terrific performers to execute them, but the Farrellys flounder here on the first count, if not the second. Zellweger, with her rosy Campbell-kid cheeks and lemonade-pucker pout, is a great foil for Carrey; she's got just enough tart pizazz to stand up to his shenanigans. Anthony Anderson, Mongo Brownlee and Jerod Mixon are effortlessly winning as Charlie's tubby, good-natured supergenius sons. Other actors, though, like the ruggedly appealing Robert Forster, are disappointingly underused.

There's a shaky vibe to many of the jokes in "Me, Myself & Irene," and it's not the result of timorousness on the part of the Farrellys. The movie is badly paced as a whole -- you don't get that carefree, cartwheeling sense from gag to gag, the way you do in earlier Farrelly comedies. Even worse, the timing within many of the jokes themselves is too flaccid; a sequence where Charlie puts an ailing cow out of its misery has an aimlessness that should work as dada, yet it just peters out to nothing.

But even though the Farrellys haven't built the greatest framework for their movie, it still amounts to much more than just a bad comedy, at least in part because of Carrey's presence. There's something both incredibly touching and annoying about his Charlie. When he catches the guys down at the local barbershop leering at a young knockout as she pushes a baby stroller along the sidewalk, he cries out in innocent outrage, "Guys, she's a mom!" -- and you're not sure whether you'd rather give him a reassuring hug or hang a "Kick me" sign on his back.

Carrey negotiates the shifts between Charlie and Hank beautifully: When Hank is about to appear on the scene, Carrey's voice deepens, and his lines start to slither out in a seductive monotone, blatantly stolen from Clint Eastwood. Carrey's astonishing physical grace comes to the fore in the scenes where Charlie and Hank struggle for dominance over Charlie's body: The sequences are a rubbery ballet of twirls, back flips and lightning-quick double takes, and Carrey doesn't go easy on himself. He knocks himself about so ruthlessly that the effect is sometimes a little brutal -- but that's part of what gives Carrey's work its gleaming edge.

Even for all its flaws, there's still a small nugget of genius, and a whole lot of warmth, at the heart of "Me, Myself & Irene." The picture is narrated in soothing storybook tones by Rex Allen Jr., the sound-alike son of the actor who lent his voice to any number of faceless Disney nature pictures, and it's a brilliant touch: There's something delightfully off-kilter about the way he outlines Charlie's mishaps the same way he'd render a play-by-play of wrestling baby squirrels.

And if nothing else, "Me, Myself & Irene" shows definitively how good-natured the Farrellys are at their core. A prominent mental health organization has protested the movie, claiming that it shows insensitivity toward the mentally ill. But it's never in doubt how much the Farrellys care for Charlie/Hank, and they make the audience care too. When we see skinny little Charlie squeezed happily on the couch between his three jolly, oversize, future-nuclear-physicist black sons, exclaiming with glee first over a TV clip of Jim Nabors singing "Blowin' in the Wind" ("That's Gomer Pyle!") and then over a hilarious, off-color Richard Pryor routine, we wish him nothing but the best life has to offer. He needs all the luck he can get. But he doesn't need our pity.

Shares